Examining the Impacts of Restricting Diversity Representation in Education

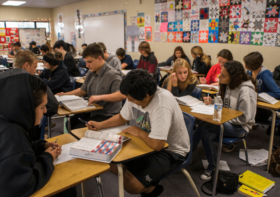

Recent actions by a Texas school district to remove diversity-related posters and displays has sparked much-needed attention. The conversation cannot stop at outrage. These moves reflect a deeper ideological project with long-term social consequences, especially for students already at the margins.

Educators and scholars must confront what’s really at stake: the active suppression of identity, history, and visibility in the spaces where children are forming their sense of self. These decisions form part of a broader effort to maintain dominant narratives by silencing difference.

Why Representation Matters

Psychological research makes one thing clear: representation shapes development. Social identity theory shows how group visibility informs self-concept. Stereotype threat reveals how underrepresentation increases anxiety, lowers performance, and distorts a student’s experience in the classroom.

Critical race theory helps connect these individual effects to structural forces. It insists that erasure is a political tool. When schools strip away the signs and symbols of diversity, they are reinscribing dominance.

Removing displays that reflect the identities of students of color, immigrants, and others does not foster harmony. It teaches students that their realities are inconvenient. It tells them that affirmation is conditional. The absence of visible diversity becomes its own kind of curriculum.

Colorblindness Is Not Innocent

Claims that removing diversity posters makes schools more “politically neutral” reflect the persistent myth of colorblindness. Colorblind ideology insists that ignoring race will eliminate racism. It does neither. It erases the conditions that make identity salient in the first place. When school walls reflect only the dominant group, the message is clear: everyone else must adapt, assimilate, or disappear.

I experienced this confusion firsthand. My mother, a woman of color, raised me to be “colorblind.” She believed it was safer that way. She avoided conversations about race and encouraged me to see everyone as the same. But growing up, I was singled out, ridiculed, and excluded.

My mother’s colorblindness left me with no identity. I didn’t understand why I didn’t belong. Her silence left me unequipped to process the colorism I was experiencing. It took years to unlearn the shame and disorientation.

What I needed was not avoidance, but the language and tools to understand who I was and why it mattered.

Colorblindness didn’t protect me. It cut me off from myself.

Manufactured Ignorance

Banning diversity displays is not a passive act. It is a deliberate decision to limit what students are allowed to know. Philosopher Charles Mills calls this “the epistemology of ignorance”—the structured production of unknowing that benefits those in power.

When educational leaders restrict access to stories, images, and histories that reflect marginalized communities, they are shaping consciousness. They are ensuring that students grow up with incomplete frameworks. This ignorance is strategic. It protects dominant narratives and forecloses empathy.

We need to ask: who benefits from these decisions? What political anxieties drive them? What histories are being avoided, and why?

What Educators Must Confront

Schools are cultural battlegrounds. The removal of diversity displays reflects an institutional choice to retreat from complexity, to avoid reckoning, and to shield students from the world they already live in.

If we are serious about preparing students for life in a pluralistic society, we must stop pretending that absence is objective. We must stop treating representation as optional.

Children form beliefs not only from what they are taught, but from what they are denied. When a school erases difference, it creates a hierarchy. And students learn exactly where they fall on it.

What Comes Next

We must call these decisions what they are: acts of erasure. They deepen confusion, silence, and mistrust. Educators, parents, researchers, and students themselves must push back—not just for symbolic inclusion, but for a cultural shift in how identity and knowledge are understood.

Representation is infrastructure. It holds up the emotional, intellectual, and social health of school environments. The removal of that infrastructure leaves students exposed, unsupported, and misinformed.

To remain silent in the face of erasure is to endorse it. The work ahead requires cultural clarity, moral urgency, and a refusal to accept institutional cowardice as compromise.